When building IoT systems, real-time data pipelines, or event-driven architectures, choosing the right messaging protocol is critical. MQTT and Apache Kafka are two of the most widely adopted technologies in this space, but they serve fundamentally different purposes despite both using the publish-subscribe model.

A common misconception is that MQTT and Kafka are competing protocols. In reality, they are complementary technologies designed for distinct layers of your data architecture. Understanding their differences helps you make informed decisions and, in many cases, leverage both for optimal results.

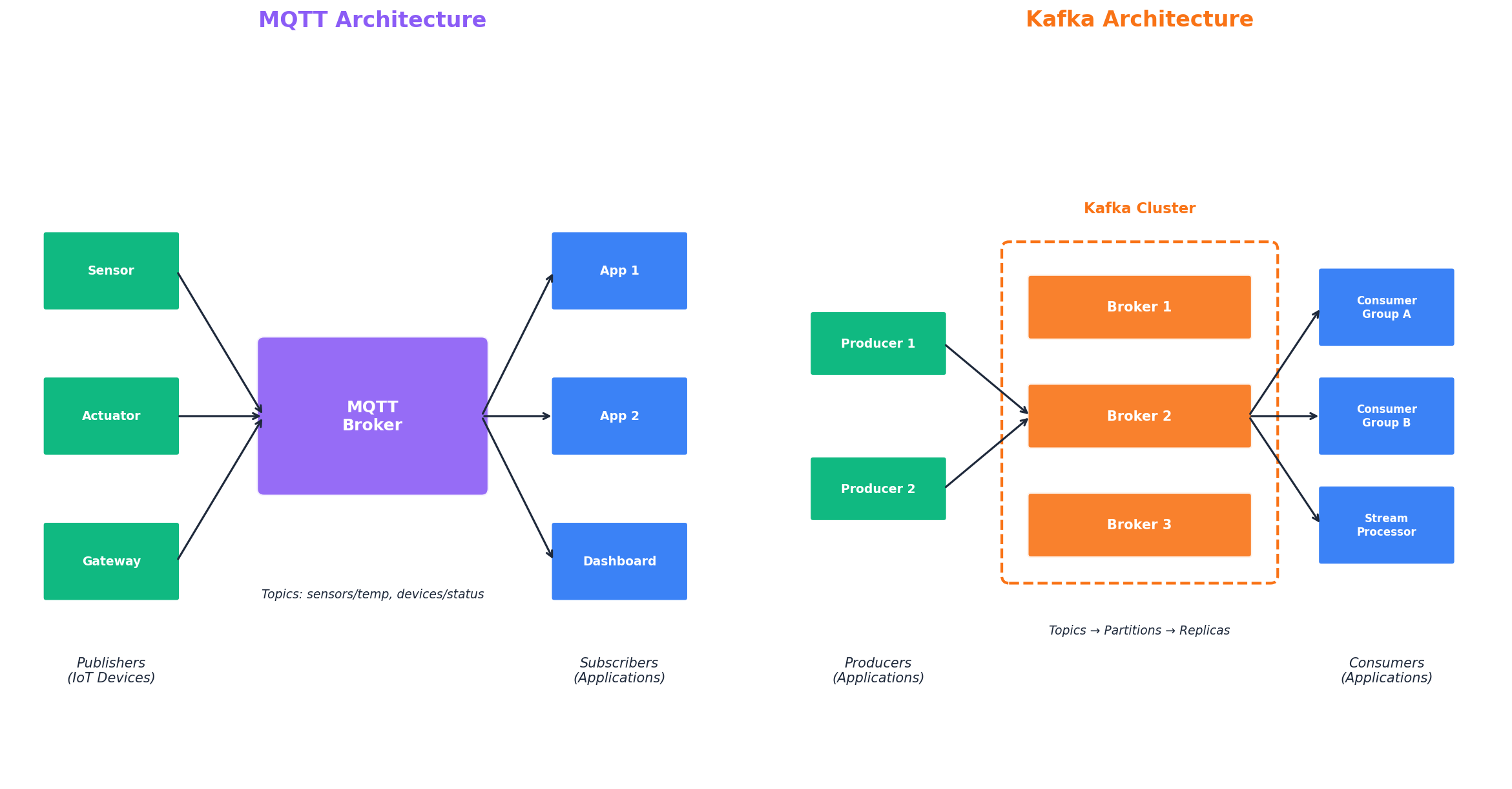

MQTT (Message Queuing Telemetry Transport) is a lightweight messaging protocol developed in 1999 for monitoring oil pipelines over unreliable satellite links. The protocol was designed to squeeze messages through terrible networks without killing battery life on resource-constrained devices.

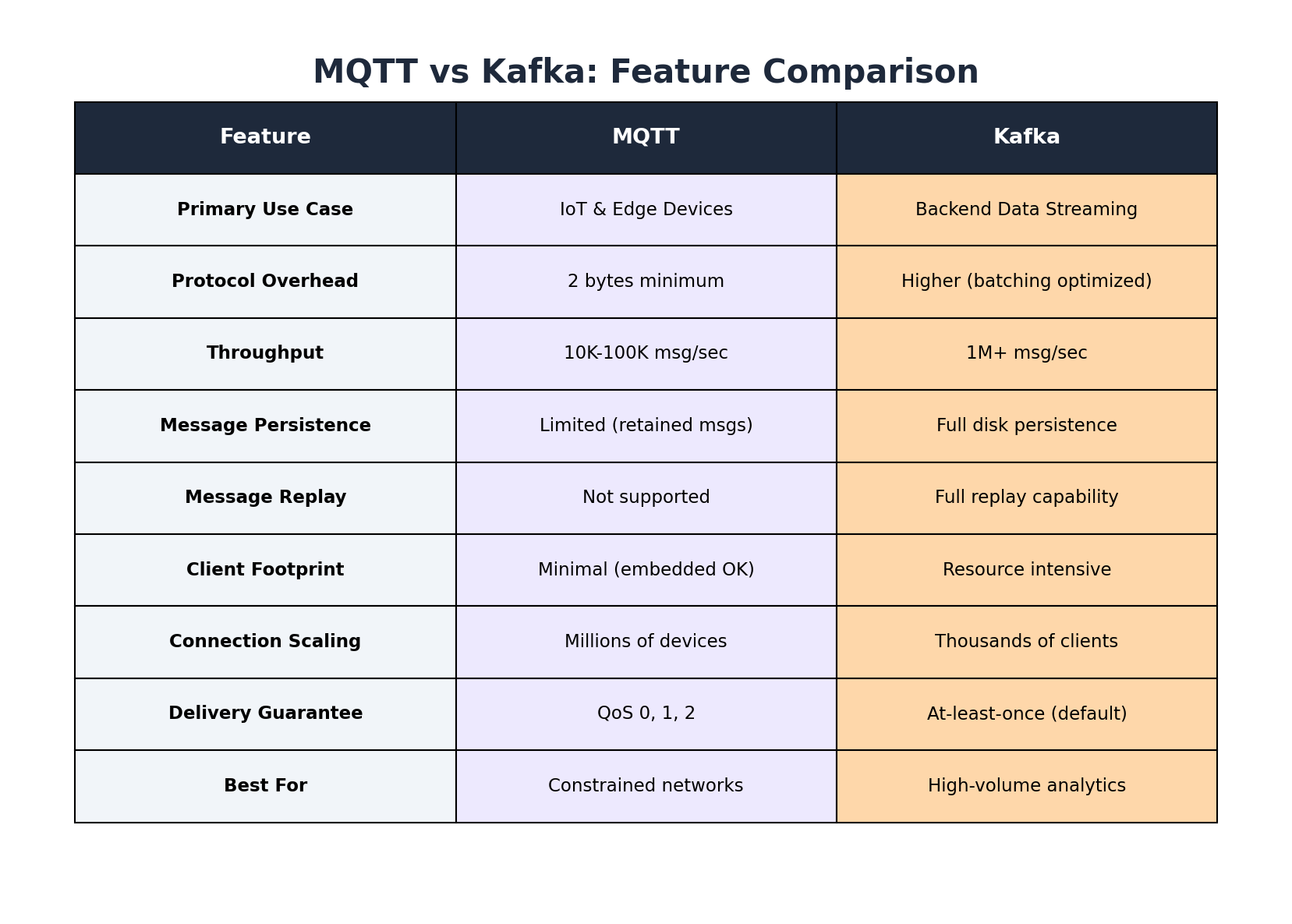

MQTT uses binary encoding with headers as small as 2 bytes, making it ideal for embedded systems with limited memory, such as an ESP32 with 520KB of RAM, or for transmitting data over expensive cellular connections where every kilobyte counts.

Key characteristics of MQTT include its minimal protocol overhead, support for intermittent connectivity through persistent sessions, and features like Last Will and Testament (LWT) messages that notify subscribers when a device unexpectedly disconnects.

Apache Kafka is a distributed event streaming platform built by LinkedIn in 2011 to handle massive activity streams and operational metrics that traditional message queues could not manage. Kafka functions more like a distributed database than a traditional message broker.

Kafka organizes data into topics, which are split into partitions. Each partition is an ordered, immutable log of messages. Producers append messages to partitions while consumers track their position using offsets. This architecture enables Kafka to achieve massive throughput by allowing multiple producers and consumers to operate on different partitions simultaneously.

The platform spreads partitions across multiple broker servers with configurable replication, ensuring that if a broker fails, another takes over immediately with no data loss.

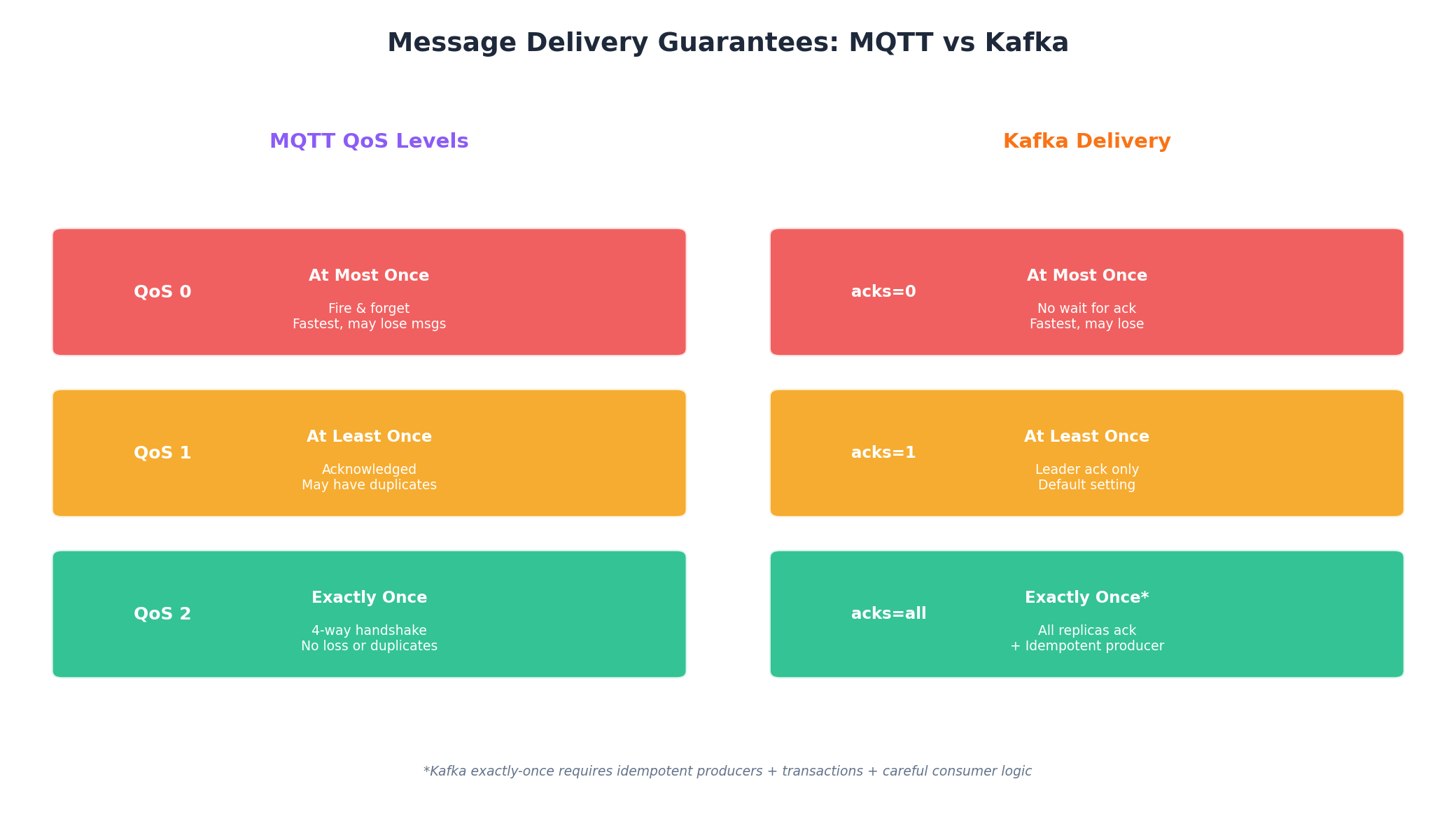

MQTT provides three Quality of Service (QoS) levels that give developers fine-grained control over delivery reliability. QoS 0 offers fire-and-forget delivery with no acknowledgment, which is fast but may lose messages. QoS 1 guarantees at-least-once delivery with acknowledgments but may produce duplicates. QoS 2 ensures exactly-once delivery through a four-way handshake, which is slower but eliminates both loss and duplication.

Kafka provides at-least-once delivery by default through producer acknowledgment settings and consumer offset commits. Modern Kafka supports exactly-once semantics through idempotent producers and transactions, though achieving this requires careful configuration of both producer and consumer logic.

MQTT brokers are not designed for long-term message storage. While brokers can queue messages for offline subscribers with persistent sessions, and retained messages provide the last known state of a topic, the protocol focuses on real-time delivery rather than historical data access.

Kafka writes all messages to disk based on configurable retention policies. You can keep messages for days, weeks, or indefinitely. This persistence model enables message replay, allows new consumers to read historical data, and supports reprocessing if analytics code needs correction.

MQTT brokers typically handle thousands to tens of thousands of messages per second, which is sufficient for IoT scenarios with many devices sending periodic data. The protocol excels at managing large numbers of concurrent connections from resource-constrained devices.

Kafka handles hundreds of thousands to millions of messages per second through its distributed architecture. However, Kafka achieves high throughput partly through batching, which can increase message latency compared to MQTT. Kafka also requires more system resources, making it unsuitable for direct deployment on edge hardware.

MQTT clients have minimal resource footprints, making them suitable for embedded systems and battery-powered devices. The protocol is designed to conserve power, especially when paired with energy-efficient physical layer protocols like LoRa or Bluetooth Low Energy.

Kafka client libraries are more resource-intensive. Establishing a Kafka connection requires considerable resources, and the platform lacks optimizations for large numbers of connections from devices that generate data sporadically.

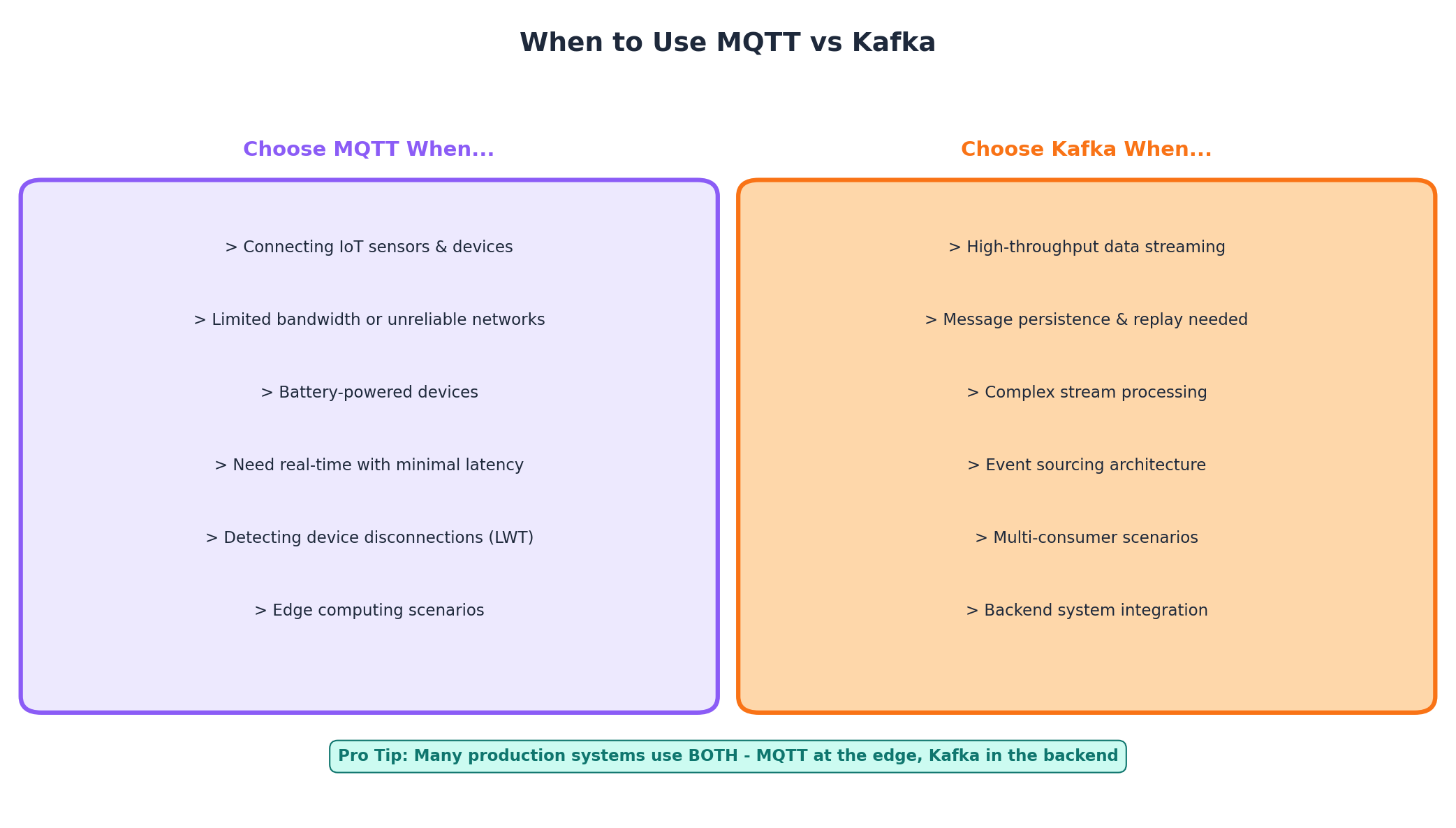

MQTT is the right choice when you need to connect resource-constrained IoT devices such as sensors, actuators, and embedded systems. It excels in scenarios with unreliable or bandwidth-constrained networks, including remote locations using satellite, cellular, or LoRa connectivity.

Choose MQTT when low power consumption is critical, such as battery-powered devices that need to stay connected for extended periods. The protocol is also ideal when you need real-time communication with minimal latency and when devices need features like Last Will messages to detect disconnections or retained messages to receive the latest state immediately upon connection.

Common MQTT use cases include smart home automation, industrial monitoring on the shop floor, remote parameter changes on machinery, and communication with mobile assets like AGVs or wearables experiencing connectivity gaps.

Kafka is the right choice when you need high-throughput data streaming between backend systems and applications. It excels at handling massive data volumes, processing gigabytes to terabytes of events per day with horizontal scalability.

Choose Kafka when you require message persistence with replay capability for analytics, machine learning, or audit purposes. The platform is ideal for complex stream processing with stateful transformations using Kafka Streams or Apache Flink, and for building event-sourcing architectures where the complete history of state changes must be preserved.

Common Kafka use cases include real-time analytics pipelines, KPI and OEE calculations across multiple facilities, data integration between enterprise systems, and scenarios requiring fault-tolerant, distributed processing of continuous data flows.

Most production systems do not choose between MQTT and Kafka. Instead, they use both protocols at different layers of their architecture. MQTT handles communication at the edge with devices and sensors, while Kafka manages data flow between central systems, analytics platforms, and data lakes.

This pattern appears across industries: MQTT at factory sites collecting sensor data, Kafka in the data center processing and distributing that data to multiple consuming applications. The integration typically involves a bridge service that forwards MQTT messages to Kafka topics, either through custom code or Kafka Connect with MQTT source connectors.

When bridging MQTT and Kafka, best practices include using MQTT QoS 1 or 2 to ensure message delivery before forwarding, leveraging Kafka's partitioning and replication for scalable and fault-tolerant message handling, and using consistent serialization formats like JSON or Avro to minimize conversion overhead.

MQTT and Kafka solve different problems in the messaging landscape. MQTT excels at lightweight, efficient communication between IoT devices and servers, making it perfect for the edge layer of your architecture. Kafka provides robust, scalable data streaming and processing capabilities for handling large volumes of data in backend systems.

Understanding these distinctions allows you to select the right protocol for each part of your system. In many IoT and real-time data processing scenarios, combining both technologies provides the optimal solution for end-to-end data flow, from constrained devices at the edge to powerful analytics platforms in the cloud.